The Evolution of Opulence: From Gilded Age Excess to TikTok Trends

April 23, 2024

Nicole Chakhalian

The Evolution of Opulence: From Gilded Age Excess to TikTok Trends

Background: The Gilded Age

In the digital age, conspicuous consumption, as theorized by Thorstein Veblen in “The Theory of the Leisure Class,” has metamorphosed into social media platforms, such as TikTok and Instagram. This article delves into the philosophical and political dimensions of Veblen’s theories, juxtaposing them with the contemporary landscape of influencers and the rise of TikTok shops. By tracing the evolution of conspicuous consumption from the Gilded Age to the present, we can unravel enduring patterns that illuminate the intersections of human behavior, societal values, and political discourse.

To establish the foundation for Veblen’s analysis of conspicuous consumption, it is important to explore the economic and social dynamics of the Gilded Age, as this era’s economic patterns laid the groundwork for the contemporary manifestation of consumption in 2024. Consumption patterns during this the Gilded Age (1870s-1900s) were deeply rooted in a philosophical understanding of social stratification and economic inequality. The emergence of what Veblen termed the “Leisure Class” marked a notable departure from productive labor to the ostentatious display of wealth through leisure pursuits, a reflection of the opulence characterizing the era.

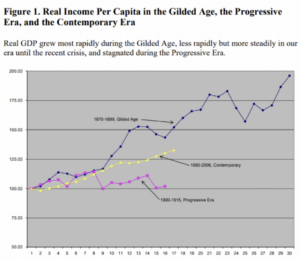

Veblen’s observations were deeply intertwined with the transformation in how individuals allocated their time and resources during the Gilded Age. As industrialization propelled robust economic growth, with the gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaging at a very strong 4.5 percent per year, there was a notable shift away from the traditional focus on productive labor to a more conspicuous form of consumption. Data from that era highlights a notable upswing in both the manufacturing and utilization of diverse goods. A prime illustration of this trend is the flourishing steel industry, serving as a robust indicator of industrialization.

The surge in steel production between 1875 and 1920, particularly in the United States, serves as a tangible manifestation of conspicuous consumption’s role in economic expansion. The flourishing steel industry during this period was not solely driven by utilitarian demand but also by the conspicuous display of wealth through the construction of grandiose buildings, monuments, and infrastructure projects which called for bessemer steel. This indicates that a substantial portion of the economic growth in the steel industry stemmed from the ostentatious consumption of materials for conspicuous purposes rather than purely functional necessity.

Additionally, the emergence of a consumer culture during the Gilded Age, facilitated by the expansion of credit and installment purchasing, further underscores the prevalence of conspicuous consumption in driving economic expansion. Despite relatively low wages for many individuals during this time, the availability of credit allowed a broader segment of society to participate in the consumption of luxury goods and leisure pursuits, contributing to overall economic growth. Moreover, historical accounts detailing the proliferation of advertising and marketing strategies during the Gilded Age provide further evidence of the significance of conspicuous consumption in stimulating economic activity as illustrated in the graph where real GDP (Gross Domestic Product adjusted for inflation) during the Gilded Age was the highest.

This reinforces the argument that conspicuous consumption, driven in part by advertising and marketing efforts, contributed significantly to economic growth during the Gilded Age.Advertisers capitalized on the desire for status and social emulation, promoting the idea that one’s social standing could be elevated through the acquisition of specific goods and services. Advertising expert Roland Marchand described in his Parable on the Democracy of Goods, “in an era when access to products became more important than access to the means of production, Americans quickly accepted the notion that they could live a better lifestyle by purchasing the right clothes, the best hair cream, and the shiniest shoes, regardless of their class.” This marketing-driven consumption fueled demand for luxury items and contributed to economic expansion driven by conspicuous consumption.

Thorstein Veblen’s Critique

For better or worse, American consumerism had begun. With this background in mind, it’s time to understand Veblen’s analysis and critique of the changes he saw in America.Thorstein Veblen, an American economist and sociologist, presented a scathing critique of the leisure class in his influential work “The Theory of the Leisure Class,” published in 1899. In this book, Veblen examined the emergence of a wealthy elite in the United States during the Gilded Age, which as said before was a period marked by rapid industrialization, technological advancement, and conspicuous consumption.Veblen argued that the leisure class engaged in conspicuous consumption, where they conspicuously wasted resources on luxurious goods and services to display their wealth and social status. This behavior, he believed, was not driven by practical utility but rather by the desire for social distinction and prestige.Veblen saw the emergence of the leisure class as a product of the social stratification inherent in industrial societies like the United States during the Gilded Age. As wealth became increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few industrialists and financiers like Andrew Carnegie and John Davison Rockefeller, Veblen argued that this elite class class used conspicuous consumption and leisure to maintain their privileged position and distinguish themselves from the lower classes causing social stratification and inequalities.

The Gilded Age, characterized by rapid economic growth and stark social inequality, played a crucial role in shaping Veblen’s critique. During this period, industrialists amassed immense fortunes through monopolistic practices, while many workers endured harsh working conditions and poverty. The ostentatious displays of wealth by the leisure class stood in stark contrast to the struggles of the working class, further reinforcing Veblen’s observations about how the social and economic implications of conspicuous consumption shed light on how status-seeking behaviors contribute to the perpetuation of social inequality. With a significant portion of wealth concentrated in the hands of the top one percent, Veblen’s analysis found fertile ground in the socioeconomic context of the time. This context not only shaped his critique but continues to influence our spending habits today.

While one may anticipate that World War II significantly influenced our spending habits, surprisingly, it is the transformative developments of the Gilded Age that fundamentally mold our consumer behavior. The post-World War II period did witness significant shifts in consumption patterns, such as the rise of suburbanization, the expansion of the middle class, and the proliferation of consumer electronics, notably though these trends can be traced back to the foundations laid during the Gilded Age.

During the Gilded Age, industrialization and technological advancements set the stage for a consumer-oriented society to emerge in the 20th century. The expansion of railways, the rise of mass production, and the growth of consumer culture all originated from this period. Thus, the Gilded Age remains a pivotal period in understanding the roots of our present consumption habits, illustrating how historical developments continue to shape contemporary behaviors and societal norms.

The Role of Social Media

Social media platforms have emerged as the contemporary canvas for conspicuous consumption. consumption. Influencers on popular platforms like TikTok and Instagram are redefining Thorstein Veblen’s leisure class concept, placing a strong emphasis on flaunting luxurious lifestyles. This trend has woven itself deeply into the fabric of our digital society, molding consumer behaviors and societal norms. According to a Pew Research Center study, a remarkable 72% of American adults actively participate in social media, highlighting the pervasive influence these digital spaces wield.

In this context, influencers play a crucial role in shaping the narrative of conspicuous consumption on social media. Through carefully curated content spotlighting opulent lifestyles, influencers foster a culture of emulation and competition among their followers. The Pew Research Center’s study supports this, revealing that a significant portion of social media users actively engage with influencer content, solidifying the notion that these digital personalities hold substantial sway over the public opinion.

Furthermore, the study explores the motivations behind social media use, uncovering that a substantial portion of users utilize these platforms with the primary goal of being seen. This aligns with the core concept of conspicuous consumption, where individuals seek to conspicuously display their wealth and social status. But why the desire to be seen? Aesthetic economics provides the answer. The contemporary market of Generation Z in the United States is characterized by a growing spending capacity. According to Business Insider’s 2022 estimate, Gen Z possesses over $360 billion in disposable income, surpassing the estimate from three years ago by more than double. This substantial increase establishes them as a prominent demographic in the current market, outpacing other generations. Moreover, this trend delves into the prevalent phenomenon of aestheticization within advanced capitalist societies, emphasizing the major role of aesthetic efforts in shaping the modern economic landscape. A defining characteristic of the aesthetic economy is the allocation of a considerable portion of the total economy to create show values; objects are no longer just produced to be used and consumed in the strict sense. This implies that a significant part of the production process is dedicated to generating values that may not be essential for individuals. The aesthetic economy represents a unique stage in the evolution of capitalism, particularly in a phase after the saturation of the private sphere with economic activity. This phase is labeled “aesthetic capitalism,” signifying that further economic growth is achievable only through the production of aesthetic values.

Building on the exploration of the aesthetic economy and its impact on consumption patterns, the TikTok store stands out as a vivid exemplar of this paradigm shift. Rather than focusing on tangible objects with inherent value, the items promoted on the TikTok store often transcend mere functionality, representing lifestyle choices and leisure streams that align with the aesthetic economy’s principles. But what are these on TikTok? Tiktok’s aesthetics are genres or ephemeral glimpses of seemingly regular life compacted into small video pieces. People may pander to their audience by displaying a certain lifestyle, fashion choice, or informal meal preparation in the wilderness surrounded by snow. All of this gives off a certain “vibe.”

Similarly, drifting down the street on a skateboard to the music of Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” while sipping on cranberry juice, as demonstrated by Nathan Apodaca in a now-famous TikTok, all conveys a particular “vibe.” The phrase “vibe” is well-known, and it serves as a placeholder for an elusive characteristic that resists precise definition—an atmosphere or aesthetic. These aesthetics are offered to TikTok viewers and enable them to make purchasing decisions. This type of behavior, in which the economy is broken down into aesthetics, is also known as “fetishized commodities.” Karl Marx, German philosopher and economist, was the first to make insights into fetishized commodities and aesthetics, stating that “value-relation of the products of labor, within which it appears, have absolutely no connection with the physical nature of the commodity and the material relations arising out of this.” In other words, our culture is becoming more and more enthralled with the symbolic appeal of the products we use rather than their functional use.

The Consequences of Society’s Buying Patterns

In a society where the act of purchasing has become intertwined with the pursuit of a curated lifestyle, it is essential to acknowledge that buying in itself is not inherently problematic. However, the means through which these purchases are financed raises critical concerns. Much like the era of the Gilded Age, the prevalence of credit cards and after pay services like Klarna in contemporary transactions echoes historical patterns. Access to these financial tools, without proper financial education and literacy, can inadvertently widen income gaps and exacerbate existing inequalities. As we navigate the allure of the aesthetic economy within platforms like TikTok, it becomes imperative to scrutinize not only what we are consuming but also how we are financing these consumption patterns and if what we may be buying serves value to us. A great example of this point is the Stanley cup trend. It’s become a cultural phenomenon: “Collectors show off shelves of their rainbow-hued, stainless steel treasures or gush over stickers and silicone doohickies to accessorize their favorite cups.” These cups were formerly unremarkable everyday objects, but their appeal has grown dramatically in recent years because of social media’s impact.

But there is a grimmer reality hiding behind the trend. An Ohio mother’s TikTok went viral, bringing attention to how this trend might encourage bullying in schools. Her child, satisfied with a $10 off-brand cup, was taunted by classmates who flaunted the more expensive Stanley counterparts. This event highlights the way we teach our children and how important it is to develop a strong sense of self-worth that extends beyond material belongings. Charles Lindsey, Associate Professor of Marketing at the University at Buffalo School of Management, commented on this, saying, “We seek out novel experiences, and while that could mean a trip to somewhere we’ve never been, it could also mean collecting different cups…From a consumer behavior standpoint, we are always incorporating variety and new things into our lives.” It is only a cup. But it symbolizes something bigger to many people. Consumer behavior is mostly driven by the attraction of novelty, but it’s important to remember that items like these cups have symbolic meaning for many people––they serve as more than simply drinkware; they are also status and identity.

This echoes the lessons written about in “The Road to Wigan Pier” by George Orwell and in contemporary discussions on aesthetic capitalism. These reveal striking similarities in the ways economic structures shape societal values and perceptions. Orwell’s portrayal of the dehumanizing effects of industrial capitalism and the struggles of the working class resonates with the commodification of aesthetics in today’s consumer culture. Much like how Orwell illustrates the exploitation and alienation experienced by workers in industrial England, contemporary discussions on aesthetic capitalism highlight how the pursuit of aesthetic experiences and lifestyles often reinforces existing inequalities and perpetuates consumerist ideals.

Where to Go From Here

In the culmination of our exploration into the evolution of conspicuous consumption, from Thorstein Veblen’s seminal critiques during the Gilded Age to its modern manifestations on social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram, one resounding truth emerges: the interplay between human behavior, societal values, and economic structures remains as intricate and impactful as ever. Veblen’s insights into conspicuous consumption and the leisure class shed light on enduring patterns that persist in contemporary society, where the pursuit of status and identity through material possessions continues to shape our interactions and aspirations. The transition from the opulent displays of wealth during the Gilded Age to the curated aesthetics of the digital age underscores the adaptability of consumerist ideals across time and mediums. As we grapple with the implications of aesthetic capitalism and the commodification of lifestyles, it becomes increasingly imperative to scrutinize not only what we consume but also how we finance these consumption patterns. The accessibility of credit and installment purchasing, reminiscent of historical trends, poses significant challenges in managing financial literacy and mitigating widening income disparities. In the end, as we navigate the allure of the aesthetic economy, it is crucial to examine not just what we consume but also how we fund these patterns and to whom our money goes.

Bibliography

Boardman, Fon W. America and the Gilded Age, 1876-1900. N.p.: H. Z. Walck, 1972.

Böhme, Gernot. Critique of Aesthetic Capitalism. Translated by E. F. N. Jephcott. N.p.: Mimesis International, 2017.

Böhme, Gernot. “Aesthetic Economy.” International Lexicon of Aesthetics, 2019. https://lexicon.mimesisjournals.com/international_lexicon_of_aesthetics_item_detail.php?item_id=66.

Catherwood, Jamie. “Gilded Age or Roaring Twenties? — Investor Amnesia.” Investor Amnesia, 2021. https://investoramnesia.com/2021/03/20/gilded-age-or-roaring-twenties/.

5 Minute Economist. “The Gilded Age: 1866-1889.” 5-Minute Economist, 2016. https://5minuteeconomist.com/history/1866-1889-the-gilded-age.html.

Fromm, Jeff. “As Gen Z’s Buying Power Grows, Businesses Must Adapt Their Marketing.” Forbes, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jefffromm/2022/07/20/as-gen-zs-buying-power-grows-businesses-must-adapt-their-marketing/?sh=597423412533.

Glenco. “Graphs & Data-INDUSTRIALIZATION: THE STEEL INDUSTRY.” The Rise of A World Power, 2014. http://unitedstatesriseofaworldpower.weebly.com/graphs-amp-data.html.

Lainer-Vos, Dan. American Journal of Sociology 116, no. 5 (2011): 1664–66. https://doi.org/10.1086/659027.

Lumen Learning. “A New American Consumer Culture | United States History II.” Lumen Learning, 2023. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-ushistory2/chapter/a-new-american-consumer-culture/.

Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. N.p.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2010.

Pew Research Center. “Demographics of Social Media Users and Adoption in the United States.” Pew Research Center, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/.

Postrel, Virginia. The Substance of Style: How the Rise of Aesthetic Value Is Remaking Commerce, Culture, and Consciousness. N.p.: HarperCollins, 2004.

Reisman, David A. The Social Economics of Thorstein Veblen. N.p.: Edward Elgar, 2012.

Semega, Jessica, and Melissa Kollar. “2021 Income Inequality Increased for First Time Since 2011.” Census Bureau, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/income-inequality-increased.html.

Smith, Aaron. “Why Americans use social media.” Pew Research Center, 2011. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2011/11/15/why-americans-use-social-media/.

TikTok. “Doggface gives the world a smile with juice, a skateboard, and all the vibes.” Newsroom | TikTok, 2020. https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-us/doggface-gives-the-world-a-smile-with-juice-a-skateboard-and-all-the-vibes.

Todd, Jennifer. “Aesthetic Experience and Contemporary Capitalism: Notes on Georg Lukács and Walter Benjamin.” The Crane Bag 7 no.1 (1983): 101-107. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30060555.